Do Animals Make Art? Issue #1: Introducing a Book Project

Some animals are hailed as 'artists' in the media, but academia remains skeptical. Will art remain one of the last signposts of human uniqueness?

Hi, I’m Jan, a research manager at ARIA – Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts, with a background in biology, psychology, and philosophy. This essay is part of a special series tied to my book-in-progress, Do Animals Make Art?, which seeks to explore this question in depth. Beyond this series, my Substack, Quirky Evolution, features reflections on what fascinates me about evolution, behavior, communication and technology—from animals to AI.

You have probably seen the footage of a tiny male pufferfish laboring for days to construct intricate geometric “mandala art” in the sand. These complex circular sculptures dwarf the fish that makes them. When Sir David Attenborough calls him “nature’s greatest artist,” it’s hard not to wonder—could this really be art?

It’s not just about pufferfish. Bowerbirds decorate their courtship arenas with colorful objects arranged in carefully orchestrated displays, sometimes even creating visual illusions.

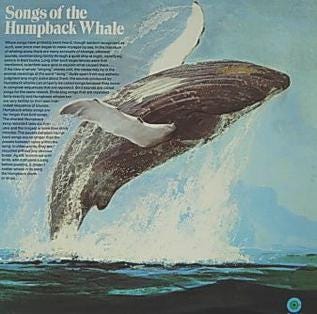

Humpback whales sing elaborate songs that humanity appreciates so much, we’ve included their recordings (alongside Mozart’s) on spacecraft travelling through interstellar space—just in case alien tourists swing by. Much like humans, humpback whales learn these tunes from each other, transmitting them between populations across the entire South Pacific. If all this feels art-like, are we humans really the only ones who make and appreciate art? Or should we rather conclude animals really do make art?

Popular Vote: Yes!

In popular media, animals like pufferfish and bowerbirds are often hailed as artists. Some scientists back this idea, too. For example, biologist John Endler—known for discovering that male Great Bowerbirds arrange objects to create forced-perspective illusions from the female’s vantage point—went so far as to suggest they are “artists” who “judge art” and therefore possess an aesthetic sense.

Beyond birds, whales, and fish, you’ll find painting elephants, dancing peacock spiders, and more. Their behaviors can seem strikingly creative, even aesthetically driven. If you love these “yes!” stories, you might be tempted to say, “Of course animals make art!” Yet, in academic circles, the dominant consensus remains that art is uniquely human.

Academic Circles: No!

When I proposed this book to a well-known university press, the editor expressed great enthusiasm, but the reviewers… not so much. One reviewer, with a background in philosophical aesthetics, critiqued the question posed in the title—Do Animals Make Art?—and thus the premise of the whole endeavor. While they acknowledged intriguing parallels between human art and animal behavior, they asserted that art is a uniquely distinctive feature of our species.

This reflects a common stance in the humanities, where art is often assumed to express the human condition, with its exclusivity taken as a given rather than something to be examined. Such assumptions align with dictionary definitions of art as “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination.” Yet, this premise is not necessarily justified. Tool-making was once considered a defining characteristic of humanity until overwhelming evidence from nonhuman animals forced us to abandon that bastion. Could the same be true for art?

Even in evolutionarily inclined fields, such as evolutionary psychology, which frequently draw comparisons between human and animal behavior, art is typically framed as a uniquely human adaptation or a byproduct of human-specific psychological traits. For instance, in The Art Instinct, Dennis Dutton writes (p. 9): “[A]nimals construct stunning objects and put on spectacular performances. Animals, nevertheless, do not create art.”

But is this framing a reflection of the evidence—or of the framework itself? Evolutionary psychology emphasizes species-specific psychological adaptations, often viewing the human mind as a product of evolutionary pressures unique to our lineage. Could this lens predispose the field to interpret art as inherently species-specific, not because of a lack of evidence in other organisms, but because of its foundational assumptions about the distinctive nature of the human mind?

A Journey

So, which is it: Yes! or No!? It’s tempting to pick a side, but both camps typically rely on assumptions rather than conclusive evidence. The “no!” side claims it’s obvious that art belongs exclusively to humans—but rarely spells out why. Is it symbolic cognition, creative imagination, or some other requirement that animals supposedly lack? When such criteria are considered, the arguments often fail to address two key points: (1) why the criterion is necessary for art and (2) the evidence substantiating its absence in nonhuman organisms.

Meanwhile, the “yes!” side often projects human aesthetic preferences onto animal behavior, without solid proof that the animals themselves experience it in a similar way.

This ambiguity isn’t new. Charles Darwin, in The Descent of Man, argued for a sense of beauty and aesthetic tastes shared even with animals as “low” as insects and spiders. In modern times, many scientists and philosophers have dismissed Darwin’s claims as overly sweeping, suggesting that animals lack the necessary sensibility and emphasizing that aesthetic tastes aren’t even universally agreed upon among humans, let alone across distantly related species.

Still, mounting discoveries in animal cognition, communication, and neuroaesthetics suggest we shouldn’t dismiss the possibility of shared aesthetic capacities—and even tastes—too quickly.

The Book’s Purpose

My upcoming book (I’ll be sharing previews here on Substack) revisits this question with the help of new research. In recent decades, we’ve seen breakthroughs in:

Animal Cognition and Communication

New findings on learning, mental representation, problem-solving, and the realistic possibility of consciousness in creatures once thought “mindless.”Evolutionary and Empirical Aesthetics

Studies that revolutionize our understanding of aesthetics as a fundamental aspect of how and why humans and other organisms process, interpret, and act on sensory information.Neuroaesthetics

Brain-scanning technologies that hint at how we and potentially other species experience aesthetic pleasure.Philosophy of Art

Classic theories—from Plato to Arthur Danto—re-examined through the lens of modern science.

Could these insights open the door to genuine “art” in nonhuman animals? Or will they reinforce art’s status as a distinctly human domain? It’s not a trivial question. If art exists outside our species, it challenges long-held assumptions about the boundaries between “us” and “them.”

The Knockout-Contest Approach

Throughout human history, attempts to define “art” have produced a dizzying array of criteria—creativity, non-utility, aesthetic intention, embodied meaning, cultural variation, aesthetic pleasure, and more. Yet even among experts, there’s no single feature that everyone agrees is necessary or sufficient for something to qualify as art. Rather than wrestle endlessly with semantics, I propose an operational approach—one that acknowledges art’s complexity and multifaceted nature while still seeking concrete points of evaluation. It’s a way to explore the question systematically without getting stuck in rigid definitions of art.

Instead of singling out a cherry-picked criterion (e.g., “art must be symbolic” or “art must be creative”), my book lays out a cumulative strategy. Because no single feature of art is universally accepted as defining, we use several overlapping criteria, eliminating any behavior that fails to meet one or more. Think of it as an open-ended “knockout contest” with multiple selection rounds, like the Turner Prize or the Eurovision Song Contest. To name just a few rounds:

Aesthetic Sense

Does the “realistic possibility” of insect subjective awareness—and their capacity to experience pleasure—also imply a realistic possibility of insect aesthetic pleasure?Mimesis (Representation)

Wild orangutans have been observed fashioning and cuddling “dolls” made from leaves, while a captive dolphin calf named Dolly once spontaneously imitated a visitor’s cigarette smoke by squirting her mother’s milk—an astonishing example of real-time mimicry. Do these instances count as representing physical reality?Art for Its Own Sake

Does dolphin bubble play—or even the playful behaviors recently noted in bees—fulfill the criterion of doing something purely for enjoyment? And, regardless, shouldn’t we distinguish between proximate factors like subjective enjoyment and ultimate (potentially hidden) adaptive functions of human art?Creativity & Culture

Should we interpret innovations in whale songs, transmitted across vast oceans, as evidence of a genuinely creative culture?

As long as an organism’s behavior or phenomenon passes all the relevant tests we can conceive—successfully surviving each selection round without disqualification—we can’t simply dismiss it as “not art.” The burden of proof is on human exceptionalism; it is to be shown art is distinctively human, not assumed.

Format: Teams & Judges

To keep it playful, I’m dividing the living world into “teams,” each represented by a signature species. For instance:

Team Pufferfish (representing non-tetrapod vertebrates—fish)

Team Bowerbird (representing nonmammalian tetrapods, such as birds)

Team Humpback Whale (representing non-primate mammals)

…and so on, culminating in Team Abramović (named after the “grandmother of performance art”) as our human benchmark.

Each team enters the knockout race, with historical heavyweights like Darwin and modern philosophers like Danto as judges. We’ll see who gets eliminated in each round. If any nonhuman team remains, we might need to rethink whether “art” truly belongs to humans alone.

Yes, it’s whimsical—like a televised art competition for the natural world. But using metaphors can help us grapple with a complex question in an accessible way. (“Plus, you can root for your favorite animals!” my AI-assistant added.)

Forum

This Do Animals Make Art?-series isn’t just a place for me to publish polished drafts—it’s a forum to explore the question together. As I post essays on each round of this fictive art contest, you are invited to:

Challenge the Ideas

If you believe animals can’t make art, tell me why. Which criterion do you consider non-negotiable?Share New Findings

If you spot fascinating studies on animal behavior, creativity, or aesthetics, share them!Offer Insights & Ideas

I’m blending philosophy, art, biology, neuroscience, and more. If something sparks an idea or a connection, feel free to reach out.

My hope is that we’ll discover—or eliminate—potential “art” in unexpected places. Is the pufferfish truly the Picasso of the seabed, or just a masterful incubator engineer?And what’s the difference between the two, anyway? Are insects mere bugs or does “imagination” really “make a bee think of honey” as Chet Baker sang? Let’s dig in and challenge our preconceptions.

Looking Ahead

In the next post of this series, I’ll dive into one of the most pivotal rounds in the Knockout Race: Aesthetics. Darwin’s surprisingly comprehensive aesthetic theory—a framework often dismissed by later biologists as naïve or flawed—will take center stage. I’ll argue that when viewed as a whole and reconsidered alongside emerging insights from neuroaesthetics, empirical aesthetics, and animal communication, Darwin’s ideas appear remarkably prescient. We’ll examine whether this reconceptualization of the aesthetic is omnipresent in the art of the human benchmark team and, if so, whether it disqualifies any of the non-human teams as a necessary criterion.

Between posts in this series, I’ll share essays on related topics and timely issues in evolution and behavior. These may include explorations of biophilia, dark behavior, cute aggression, and the emerging notion that nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution information.

As we look to the future, things are expected to get too weird to ignore. Technology is becoming more life-like, biology more engineered, and the boundaries between the organic and the artificial are blurring in fascinating ways. These transformations challenge the boundaries we’ve traditionally drawn between the natural and the human-made—boundaries that this series also questions in its exploration of art across species. I’m keen to explore the quirks and implications of these changes.